I’m a wee bit of a geek. There are scores of ways to prove this, though the one most readily at hand is the fact that behind me, on my TV, sits a paused episode of

Battlestar Galactica. The fifth episode in two days. By the way, I’m at work.

I’ve been a geek for a good long while, ever since my father took me to see

Star Wars when I was five. It kindled in me a love for science fiction that has not dimmed. (Despite the fact that, for all its lasers, space fighters, and lightsabers,

Star Wars isn’t science fiction. There is no science is

Star Wars—and, yes, I’m wholly disregarding that midichlorian bullshit. In truth, it’s Historical Religious Fiction. The Force is the axis upon which the

Star Wars Universe turns, and the Force ain’t science. It’s hope. It’s faith. And while the two can peacefully coexist, let’s not go confusing one for the other. Like certain heads of state.)

When I was a junior in college, one of my writing professors suggested that I enter this writing-for-TV competition sponsored by Gary David Goldberg’s Ubu Productions (“Sit, Ubu, sit. Good dog.”) I wrote an episode of the only TV show I watched on a regular basis:

Star Trek: The Next Generation. Remember, geek.

They must not have gotten many submissions, or the other students who entered wrote episodes of

Late Night with David Letterman, because I won. (I say this because, upon re-reading that episode again recently, it’s not very good. Then again, I was 20. No one knows anything when they’re 20. Unless you were of “the greatest generation.” They knew how to defeat world-threatening evil.)

I spent the summer between my junior and senior years in Los Angeles, on the Paramount lot, as a writing intern on

Brooklyn Bridge (the show that Ubu was producing at the time) and

Star Trek. My time on

Brooklyn Bridge was relatively uneventful: By the time I got there, they already had all the scripts they were going to need for the season. So there was little for a writing intern to do besides hang out on the set and eat muffins. Or bagels. Or the occasional carrot stick if all the muffins and bagels were gone.

And, as has been said by other, smarter people—like William Goldman—the first day you spend on a live soundstage is amazing. Every other day is boring as shit. The only day that really held any excitement was the one where Gary decided he wanted to take a picture with me on the set. They stopped shooting for a minute and Gary and I walked to the center of the set, a kitchen, if I remember correctly. The lights were hot, the crew was getting itchy to move on, the actors were watching. And then, Marion Ross—who was playing the family matriarch—said “Oh, look at the poor dear, he’s gonna faint.” Mrs. Cunningham was razzing me. Cool.

After a month, I moved over to

Star Trek. Dream come true. When I got there, one of the production secretaries was my “handler,” and I told her, point blank, “I want to get a picture of myself in the captain’s chair. Is that gonna be possible?” She wasn’t sure, but she’d find out.

Now, there was much more to do on

Star Trek. This was 1992.

The Next Generation was going gangbusters, and they were launching

Deep Space Nine. Heady days on the final frontier. I sat in on production meetings, a few pitches, a lot of story-breaking sessions, but what I did most was read scripts. See,

Star Trek was, at the time, the rare TV show that accepted unsolicited submissions. Anyone could write a script and send it in for consideration. And there were days were it seemed like anyone did. Nothing made me want to be a better writer more than reading so many bad specs.

All in all, it was a fantastic summer. Met some terrific people, some of whom are still close friends today. Learned an awful lot. Was mistaken for someone else by Steve Guttenberg, who greeted me with a hale and hearty handshake while just walking the lot. Was hit by a bike-riding Scott Baio, who creamed me while taking a corner at high speed. Charles, apparently, is also in charge of the right of way.

Only visited the

Next Generation set once. On my second to last day, I asked about “the chair” again. I was told that Patrick Stewart was very possessive of the chair, and didn’t really like other people sitting in it. But there were some VIPs taking a tour, and I could tag along. We walked through the corridor-and-a-half they used for every hallway on the Enterprise. Passed Sick Bay. Breezed through the Bridge. I waved hello to the chair.

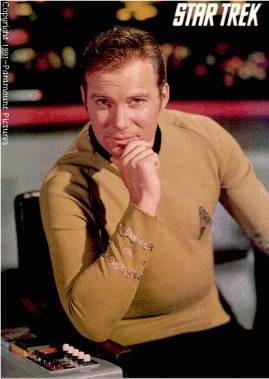

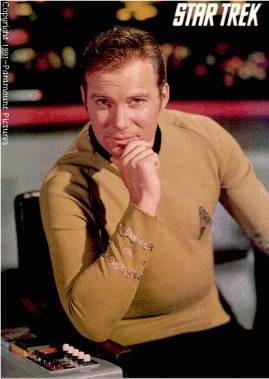

On our way out, I spied something off to my left. It was a set that was due to be struck. Only half a set, really, because they only needed it for one angle in the show it was for. The lights weren’t on, but I knew exactly what it was.

The bridge of the Starship Enterprise.

James T. Friggin' Kirk’s Enterprise.

They did this episode, I can’t remember the name (I’m not that much of a geek), and I don’t feel like looking it up, but it was the one where they unfroze Scotty from some transporter buffer. He was feeling lonely, out of time, so he went to the Holodeck and created the place he felt most comfortable, the bridge of the NCC-1701. (Why an engineer wouldn’t have felt more comfortable in, I don’t know,

engineering, was never adequately addressed.)

Before anyone could stop me, I walked over and sat in the Captain’s Chair. In Kirk’s Chair. (Don’t give me that “It wasn’t really his chair, that one is in the Smithsonian” hooey. In a land where everything is fake, one thing is as real as the next.)

I am a geek. Oh, yes. And I left the ass-groove to prove it.

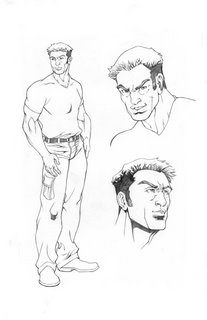

Dashing. Handsome. Fit. More than a little cranky.

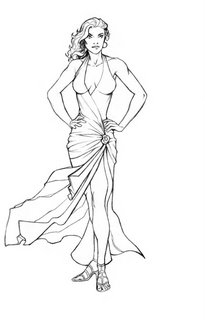

Dashing. Handsome. Fit. More than a little cranky. Mysterious. Independent. Hot.

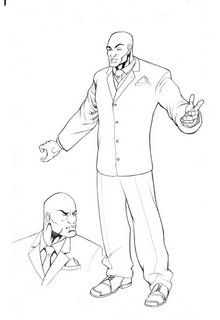

Mysterious. Independent. Hot. To quote Gene Wilder, "What's a dazzling urbanite like you doing in a place like this?"

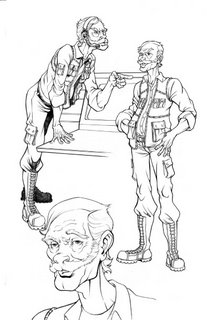

To quote Gene Wilder, "What's a dazzling urbanite like you doing in a place like this?" Because every team needs a doddering Great White Hunter.

Because every team needs a doddering Great White Hunter.